As the quiet and sunny days of October fade into the dreary days of early November, the first hints (or blasts) of winter descend upon the northern United States.

While other regions of the country may have their fair share of strong storms during the first weeks of November, few evoke the same legends as the powerful systems that batter the Great Lakes states.

Storm Characteristics

These storms form and are guided by the jet stream, which flows from west to east and encircles the midlatitudes. This gives these storms the technical name mid-latitude cyclones.

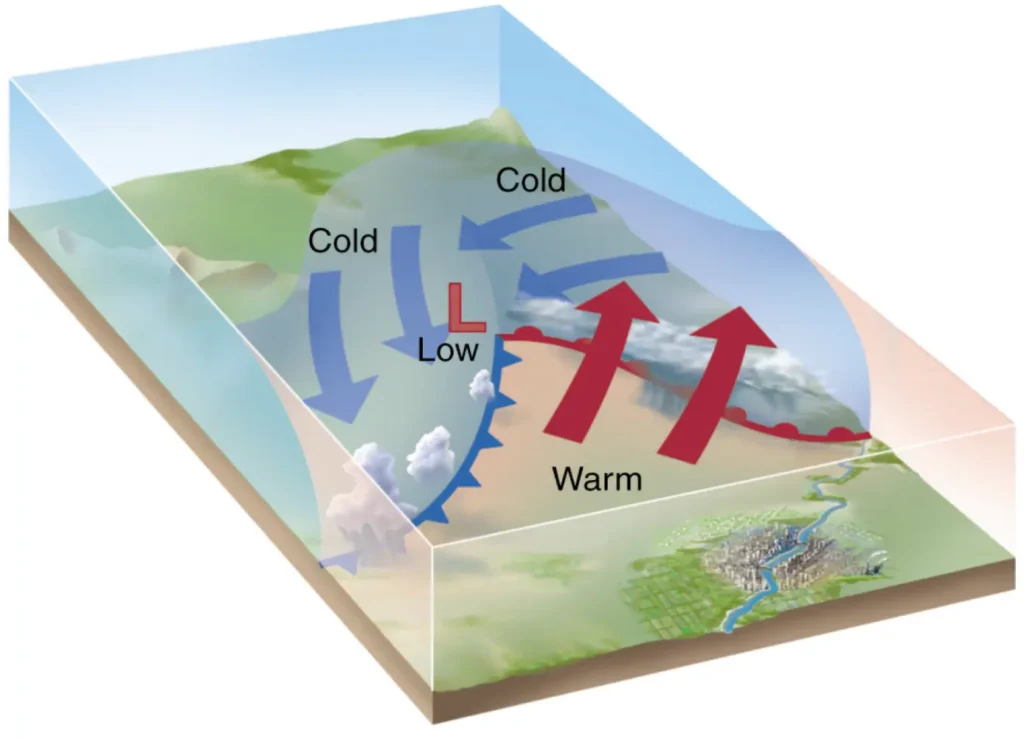

Mid-latitude cyclones are often organized, intense low-pressure centers with fronts separating air masses with stark temperature differences.

Warm fronts often stretch out ahead of the storm, separating the warm sector located south of the storm center. Cold fronts usually follow behind the system, bringing in a blast of frigid air from the north. In the hours following these storms, temperatures can drop by more than 40 degrees Fahrenheit!

Why Early November?

As fall begins to fade to winter, a chill begins to settle into the northern U.S. The length of daylight decreases noticeably, causing a change in atmospheric patterns across the midlatitudes because the temperature difference between the northern states and the still-mild southern states grows larger.

This large temperature contrast can lead to instability in the atmosphere, intensifying storms.

Regionally, the water temperature of the Great Lakes is warmer than the air at this time of year — often by as much as 15 degrees. The warm lakes add energy and moisture to the atmosphere, further enhancing storm strength.

The Perfect Storm

The frequency of these often deadly winter-like storms is highest in the Midwest during the first two weeks of November. The majority of deaths associated with these storms are sailors or boaters.

The timing hits during the final legs of the shipping season on Lakes Michigan and Superior; storms of similar strength that may come later in the month would have fewer boats to threaten, making less of an impact.

The strong winds of these storms create significant waves: sustained winds of 40 miles per hour could create a wave height of 25 feet, high enough to capsize large ships.

Due to lake temperatures near 40 degrees, survival times for those thrown into the water may only be one to two hours.

Memorable Events

Over the last 110 years, Wisconsin has experienced several memorable November storms on or about the eleventh day of the month.

The Great Blue Norther

On the morning of November 11, 1911, a potent winter storm developed over Missouri. Traveling eastward, the storm’s low-pressure center intensified as it approached western Lake Superior, with a blast of cold arctic air following on its heels.

This storm has become known as “The Great Blue Norther of 11/11/11” due to the dramatic temperature drops seen across the northern and central United States.

Madison reported a daily record high temperature of 70 degrees in the afternoon of November 11 before the cold front came through, dropping temperatures by 50 degrees before midnight! The mercury continued to fall through the night, bottoming out at 7 degrees — a record cold temperature for November 12.

This 63-degree drop remains the largest recorded in Madison and most likely in Wisconsin.

As the potent cold front met unstable, warm air, severe storms developed.

An unseasonal and powerful F4 tornado caused extensive damage to eastern Rock County. The tornado killed nine and injured 50.

Within an hour of the tornado, survivors faced blizzard-like conditions and temperatures near zero.

Armistice Day Storm

In November 1940, a powerful storm moved into the Pacific Northwest. This storm system intensified as it moved eastward across the Plains before taking a turn toward the Great Lakes.

To residents of the Midwest, this storm has become known as the infamous “Armistice Day Storm of 1940,” as it moved through the region on November 11, which was Armistice Day, now known as Veterans Day.

On the morning of the eleventh, the low-pressure center was passing over Des Moines, Iowa. Strong winds from the southeast ahead of the storm pumped unseasonably warm air into Wisconsin.

However, by the morning of the twelfth, the storm had reached Lake Superior, and a sudden wind shift behind the cold front caused temperatures to plummet.

The temperature in Milwaukee had reached 58 degrees on the eleventh, before falling to 16 degrees — a 42-degree drop! Madison and La Crosse registered 41-degree drops within the same 24 hours.

In the even colder northern counties of Wisconsin, between nine and twenty inches of snow fell. Totals over two feet were seen even farther north in Minnesota.

To boot, winds whipped the region. Gale-force winds from the southwest caused the water level of Lake Michigan at Chicago to drop 4.8 feet as water was pushed away from shore.

The public was caught unprepared for the rapidly changing weather.

As many as 157 people died due to hypothermia across the Midwest, including 13 in Wisconsin, many of whom were duck hunters along the Mississippi River. Thousands of cattle also perished. On Lake Michigan, three freighters sank, with 59 sailors losing their lives.

The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

The November storm of 1975 is perhaps the most well-known, largely thanks to Gordon Lightfoot’s song memorializing the event. This storm was responsible for sinking one of the largest ore carriers on the Great Lakes, leading to the nickname “The Edmund Fitzgerald Storm”.

The Fitz left the port of Superior, Wisconsin, bound for Detroit on November 9, 1975, as a storm was brewing in the Plains.

The system reached Lake Superior near Marquette, Michigan, on the morning of November 10. The storm had strengthened significantly and was accompanied by strong winds that gusted over 70 miles per hour in parts of Michigan.

As the storm crossed Lake Superior during the afternoon of November 10, it passed over the ill-fated Edmund Fitzgerald. It wasn’t until evening, when the wind shifted from northeast to northwest, that the ship was doomed.

Waves 12 to 16 feet were reported by a ship that was several miles from the Fitz. The 729-foot-long S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald, on the eastern end of Lake Superior, lost its crew of 29 men and 26,000 tons of taconite.

Shifting Storms

Over the last century, the frequency of these powerful early November storms appears to be decreasing.

As late autumn and early winter weather has become warmer, the temperature difference between northern and southern regions has become less pronounced.

The tracks of these cold-season storms are shifting northward, which could lead to precipitation changing from snow to rain or a wintry mix.

Though their frequency is decreasing, the intensity of the early winter storms could increase in the future as the waters of the Great Lakes grow warmer.

Fortunately, the number of lives lost on the Great Lakes has decreased over the last 150 years since the establishment of the National Weather Service. Advances in weather observations, including radar and satellites, make for more accurate weather and lake forecasts. Forecast communication has been emphasized in recent decades to improve public awareness of potentially dangerous weather conditions.

This is a product of the Wisconsin State Climatology Office. For questions and comments, please contact us by email (stclim@aos.wisc.edu) or phone (608-263-2374).