Here in Wisconsin, cranberries are extremely popular items on the holiday menu: as fresh relishes, sauces, juice, frozen products, dried snacks, or incorporated in other dishes.

The popularity of the Wisconsin-native fruit has made it the state’s largest fruit crop in terms of both quantity and economic value.

Wisconsin’s Industry

Wisconsin became the nation’s primary cranberry producer in 1994 when it surpassed Massachusetts. Now, the Badger State’s total production is more than twice that of second-place Massachusetts!

In 2024, Wisconsin produced nearly 5.5 million barrels of cranberries, approximately 61 percent of the national crop. The state’s production peaked in 2016 when 6.1 million barrels were produced. The industry’s economic impact on the state is valued at nearly one billion dollars, employing as many as 4,000 people.

History of Wisconsin’s “Crane Berry”

Cranberries are native to the temperate climate of North America, including the Midwest and East Coast. Native Americans, such as the Ho-Chunk in the Central Sands region of Wisconsin, harvested cranberries (or hoocake, as they called them) from wild marshlands for food, medicine, and red or purple dyes for fabrics. Euro-American settlers purchased cranberries from the Ho Chunk as early as 1829. Settles renamed the berry the “crane berry” because its plant stem and blossom resembled a sandhill crane.

Commercial cranberry growing in Wisconsin began near Berlin (Green Lake County) in the 1850s. Initially, ditches were dug around existing plants to encourage growth, but frost, drought, pests, and diseases often limited production.

In 1867, the state legislature passed the Cranberry Law, which granted cranberry growers the statutory right to construct dams to develop bogs, thereby encouraging the cultivation of cranberries.

The Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association (WSCGA) was founded in 1887 by early cranberry growers to address challenges, such as water usage and market potential. The group continues to provide educational resources for growers, as well as promotes the many cranberry festivals for the public.

The Bog Regions

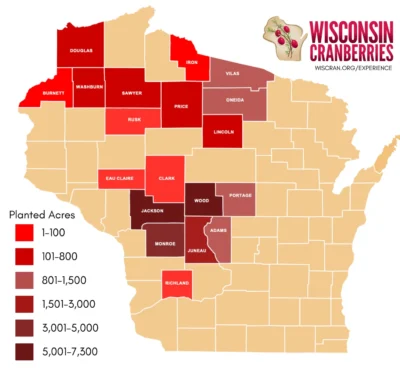

Approximately 250 growers produce most of Wisconsin’s cranberry crop primarily on family farms, covering roughly 20,000 acres.

More than two-thirds of the state’s commercial cranberry crop is grown in central Wisconsin. A secondary region of cranberry production can be found in the far northern counties.

Most of the cranberry counties in central Wisconsin have thick sandy soil that covered the lakebed of a large periglacial lake that formed along the western edge of the bay of Green Bay at the end of the last Pleistocene Ice Age, approximately 18,000 to 14,000 years ago.

Cranberry-producing counties in northern Wisconsin are also covered by sandy soils that were part of the glacial outwash from the last glaciation.

In both regions, the vast layers of sand and gravel are relatively flat and poorly drained, which allowed for the development of acidic soil. This is ideal for cranberry bogs, as other plants struggle to grow in acidic conditions, eliminating competition for the cranberry vines. The marshes of the region also provide reliable and substantial sources of water for the bogs.

Built for the Cold

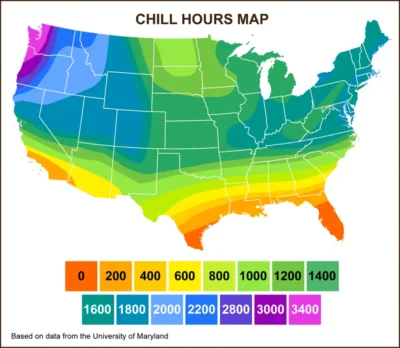

As Wisconsin natives, cranberries can easily withstand the state’s cold winters. In fact, the plant requires a sufficiently long period of winter dormancy with temperatures of 45 degrees Fahrenheit or colder to store energy and prepare to produce fruit for the next growing season.

This chilling requirement can be quantified by the metric called “chill hours,” defined as the amount of time that plants are exposed to temperatures between 32 and 45 degrees during the winter.

Wisconsin’s climate has historically provided the 650 chill hours necessary for optimal cranberry production; however, this cycle could be disrupted by the state’s warming winters.

The Midwestern Regional Climate Center provides an interactive Chilling Hours Tool that allows the tracking of chill hour accumulations at varying locations. This information can help determine the expected success of a cranberry crop.

The Growing Season

Contrary to popular belief, cranberry plants do not grow in water, as the vines are relatively intolerant of water and grow only in well-drained dry marshes with sandy soils.

Bogs are typically flooded in the autumn, sometimes for frost protection, but more often for harvesting. This makes it easier for machines to collect the buoyant berries off the plant vines.

Bogs usually remain flooded through the winter to protect the cranberry plants from the harsh wind and cold of winter.

Water is drained from the bogs before the spring growing season to allow the plants to flower and produce fruit. Then, sunshine becomes crucial for stimulating the plant’s buds. By mid-spring, at least 13 hours of sun per day are necessary for successful buds.

Blossoms typically begin in mid-June, with small berries usually appearing in July. Cranberries prefer temperatures between 60 to 80 degrees during the summer for optimal growth.

Abundant sunlight during the growing season also promotes the red color in the berries, which is a key factor in quality and market value. The cool conditions of early autumn deepen the red pigment of the fruit and help create its antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.

Historically, Wisconsin cranberries often lacked the desired vibrant red color due to the short growing season. The Plant Breeding and Plant Genetics program at the University of Wisconsin—Madison developed an early-maturing and colorful cranberry hybrid named “HyRed” that contains more red pigment. This hybrid allows state growers to harvest an attractive product before autumn frosts.

The main harvest season in Wisconsin typically occurs from late September through October, but can sometimes extend into mid-November.

Weather Impacts on Cranberries

While winter cold during hibernation is essential for plant development, extremely cold winter weather can be detrimental to dormant buds and vines.

During the winter months, a protective layer of ice forms over the flooded bogs, keeping the water temperature consistently around 28 degrees. However, if warm winter weather keeps the ice from forming, plants become susceptible to temperatures that are too cold for them to survive.

Erratic conditions in early spring can stunt the growth or even kill the plant. Early spring frosts may occur when the cranberry plants are most vulnerable, and late spring frosts can damage the plant’s emerging flowers.

Subfreezing nights too early in the fall season can damage immature fruit, limiting the time that the fruit can ripen.

Several other weather-related factors can affect Wisconsin’s cranberry crop. Excessive rain events during the growing season can lead to high humidity, which promotes disease, fruit rot, and the growth of competing plants such as moss. On the other hand, extended spells of very hot summer weather can stress the plants and reduce yield.

Bog Impacts on Weather

The sandy, low-lying nature of the state’s bog regions can create micrometeorology — localized weather conditions that differ significantly from other surrounding areas.

Bogs tend to be good radiators, releasing a lot of the heat that they absorbed during the daytime. Temperatures of bogs may fall below freezing while nearby areas may report temperatures above freezing. The valley-like topography of bog regions makes them even more susceptible to cold temperatures.

Daytime temperatures can also stay cooler than the surrounding areas, due to evapotranspiration of the moist soil.

The Value of a Good Forecast

Cranberry growers in Wisconsin are extremely dependent upon reliable and timely weather forecasts that alert them to possible frost and freeze conditions through the growing season.

More than half of Wisconsin’s cranberry crop was lost to frost in August 1904: weather observers in Jackson County reported subfreezing temperatures on August 18, 1904.

This got the attention of the Wisconsin district weather forecaster for the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) district office in Milwaukee. The office began issuing cranberry frost advisories to protect the state’s cranberry crop from damaging frost as part of the USWB’s mission to provide specialized agricultural forecasts.

Today, the National Weather Service Milwaukee/Sullivan Office has created a Frost and Freeze Decision Support Tool that allows growers to view fine-scale frost probabilities based on temperature and wind speed. These products are updated twice daily from March through October.

Wisconsin’s Environmental Mesonet (Wisconet) has worked to grow the state’s network of weather stations to provide research-grade weather and soil data to Wisconsin residents. This local data has become invaluable to cranberry growers as they make decisions about irrigation, fertilizing, and frost protection.

The Future of Wisconsin Cranberries

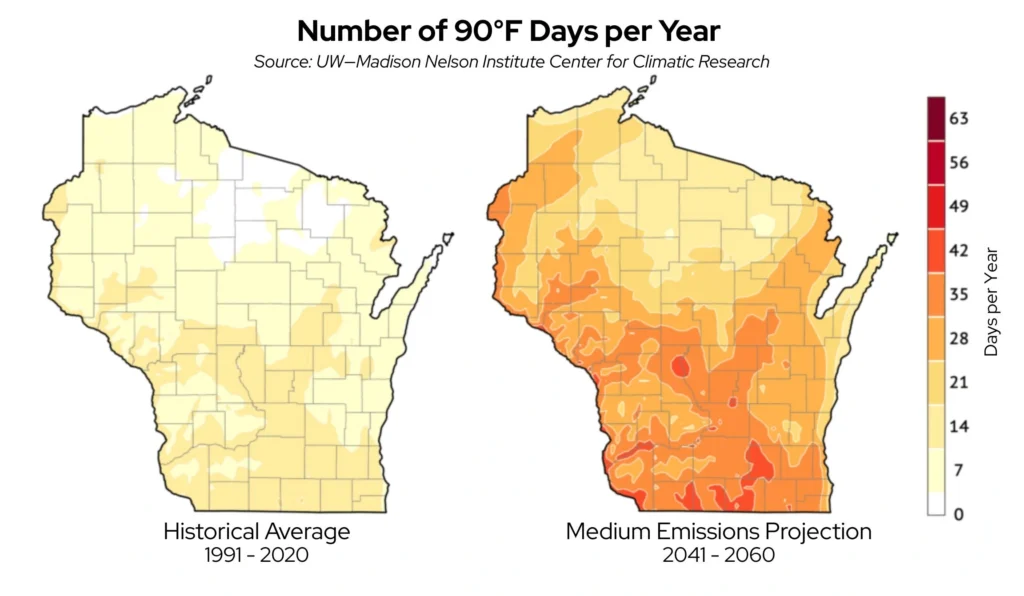

The cranberry growing season has changed as Wisconsin’s climate has warmed in recent decades. Peak bloom dates are now coming a few days earlier than in the past, and the harvest season has more frequently stretched later into November.

Milder winters could threaten the ice cover that insulates vines during dormancy, along with increased pressure from pests.

Warmer summers could also impact fruit quality. Wisconsin has yet to see an increase in days reaching 90 degrees or higher, but that change is expected to occur in the coming decades. Exposure to too high temperatures and scorching sunlight can damage the fruit, resulting in “cranberry scald.”

However, growers have found some ways to adapt to these changes through improved frost protection, water management techniques, and pest and disease control. New berry varieties have also been developed to withstand some of these more extreme conditions.

This is a product of the Wisconsin State Climatology Office. For questions and comments, please contact us by email (stclim@aos.wisc.edu) or phone (608-263-2374).