Warm and wet conditions rounded out spring 2024 in Wisconsin, alleviating drought conditions and sparking severe weather.

Warmth Continues

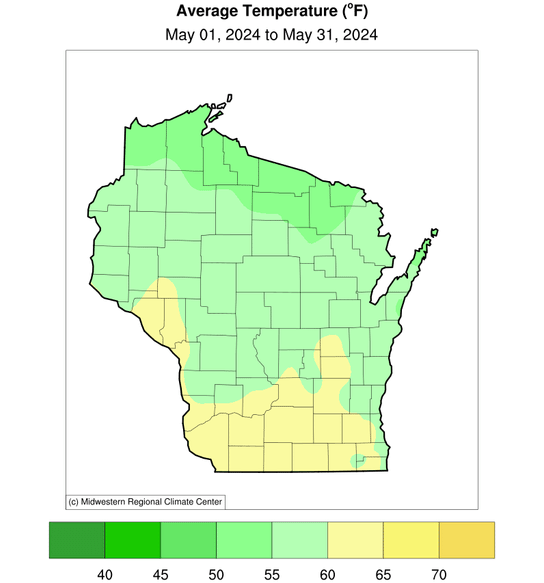

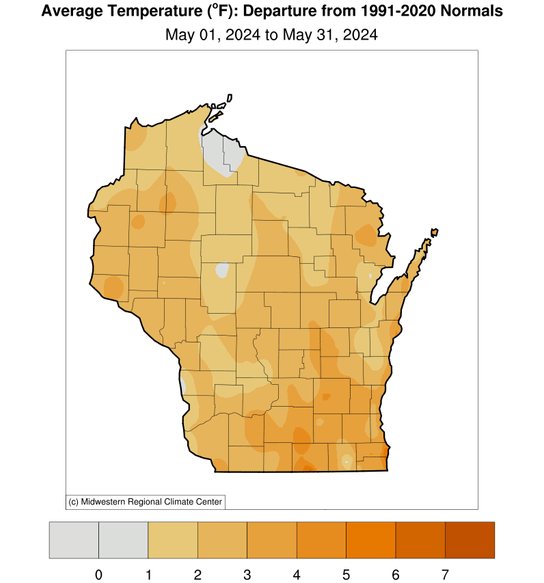

May continued Wisconsin’s monthly warmer-than-normal temperatures. Last month’s statewide temperatures averaged 57.7 degrees (Fahrenheit), which ranked 28th warmest among all Mays since records began in 1895. Northern Wisconsin averaged a mild 50 to 55 degrees or 1 to 2 degrees above the 1991–2020 normal, but in the south temperatures were a considerably warmer 60 to 65 degrees, 3 to 4 degrees above normal (Figure 1).

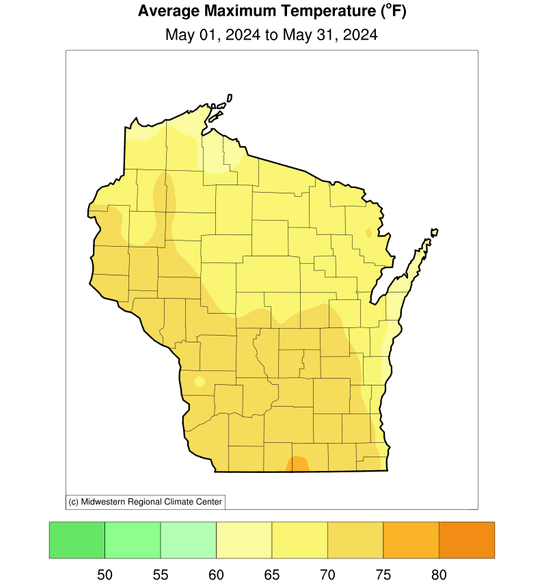

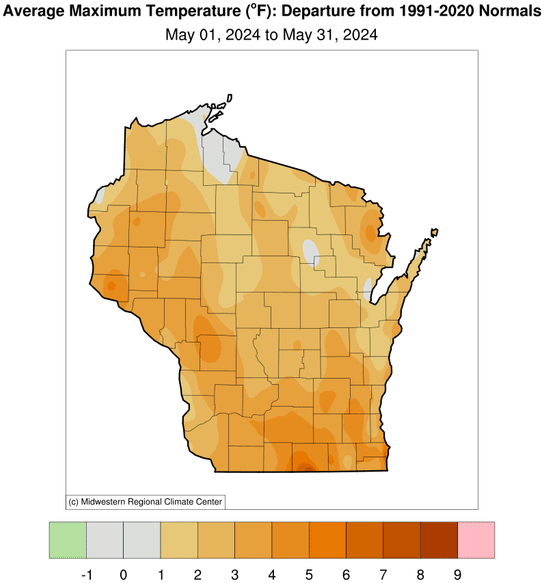

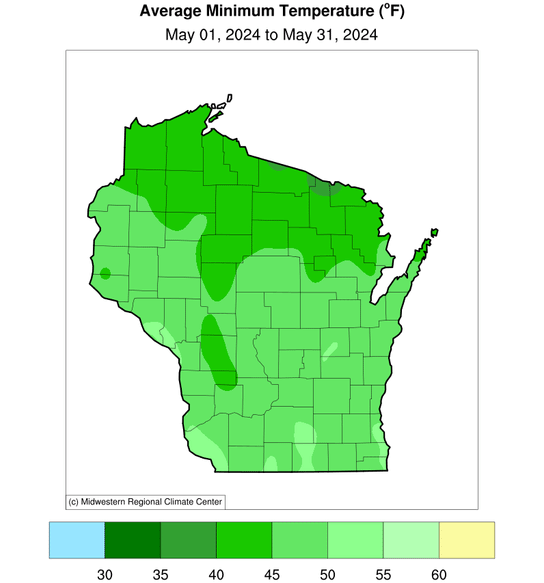

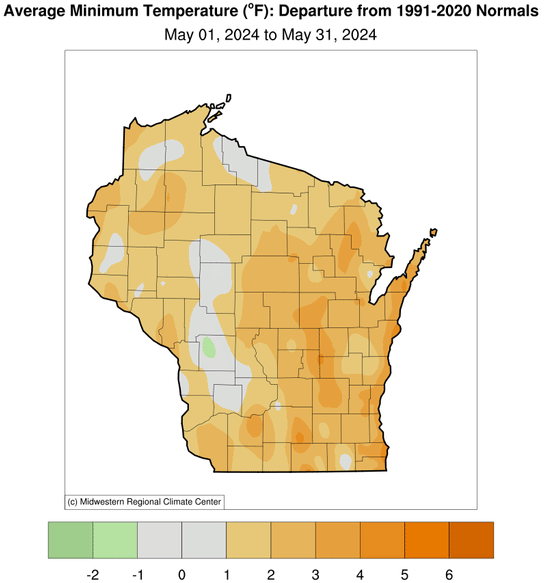

Both daily maximum and minimum temperatures were above normal. Daytime highs averaged 65 to 75 degrees from north to south, while overnight lows sat around 40 degrees in the north to 50 degrees in the south (Figure 2). Extreme temperatures ranged from 91 degrees at the Boscobel Airport on May 18 (Wisconsin’s first 90-degree occurrence this year) to 24 degrees in Hurley on May 5. Fortunately, this May was much more comfortable than in 1934, when Wisconsin endured its record high May temperature of 109 degrees in Prairie du Chien.

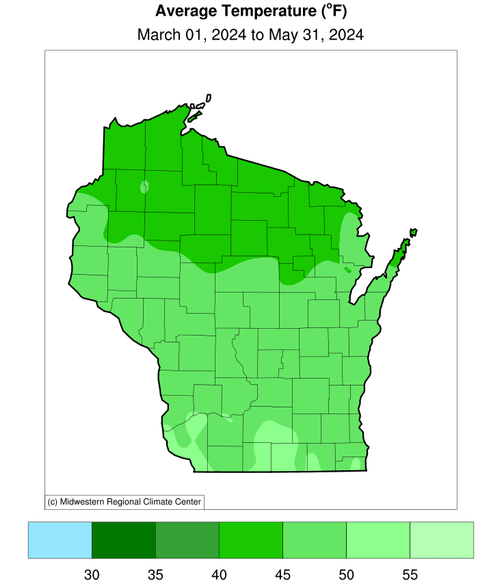

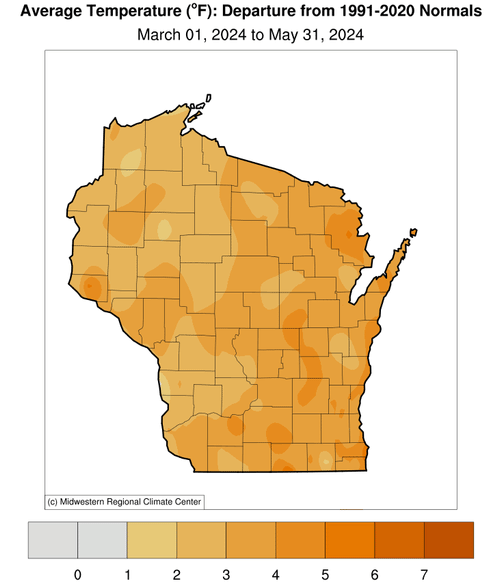

Despite the ups and downs in temperatures, the entire spring (March through May) ended an impressive 3.1 degrees warmer than normal with an average of 46.1 degrees (Figure 3). Compared to all other springs on record in Wisconsin, this spring ranked in a tie for 7th warmest. The highest temperature Wisconsin saw this spring was the 91 degrees recorded this May in Boscobel, while the lowest was -8 degrees on March 1 in Butternut.

Exceptionally Soggy

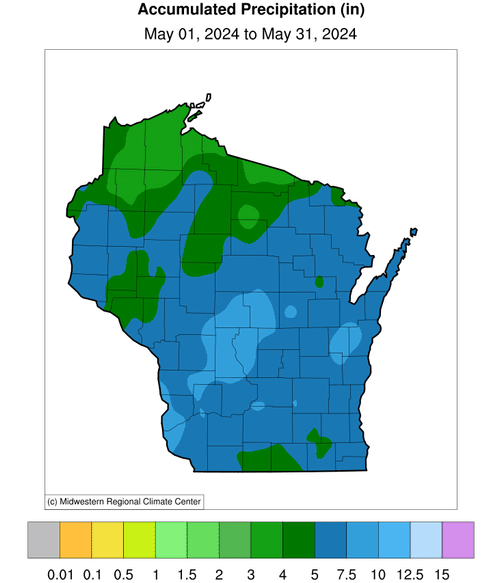

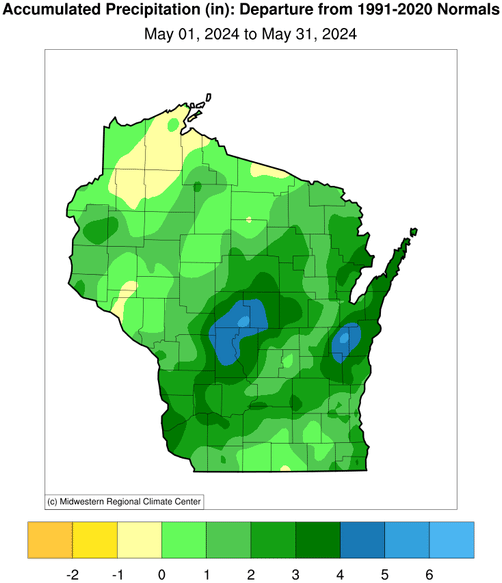

May started wet and became even wetter as the month went along, culminating in some very heavy rainfall during the final 10 days. The statewide average precipitation during May was a hefty 5.52 inches, which exceeded the 1991–2020 normal by 1.59 inches and by a remarkable 40 percent. In fact, the month ranks as Wisconsin’s 10th wettest May on record.

The central portion of the state was soggiest, especially the Central Sands region encompassing Wood, Portage, Juneau and Adams Counties, whose monthly rainfall total exceeded normal by more than four inches (Figure 4). This area and east-central Wisconsin (from Fond du Lac County northeast to Door County) received more than double the normal amount of May precipitation.

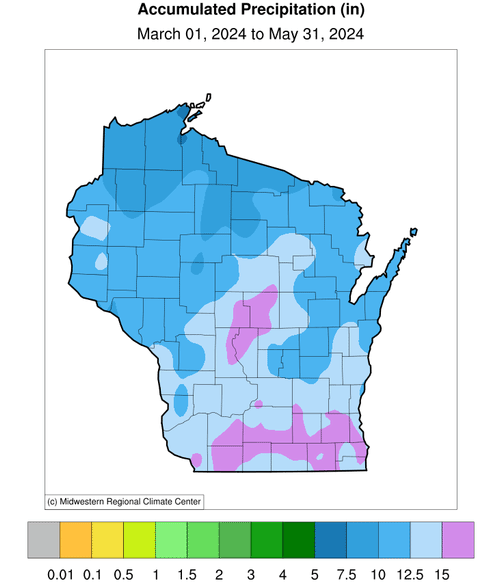

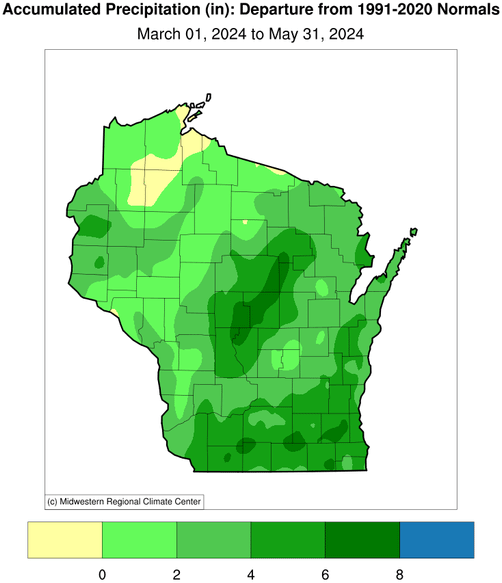

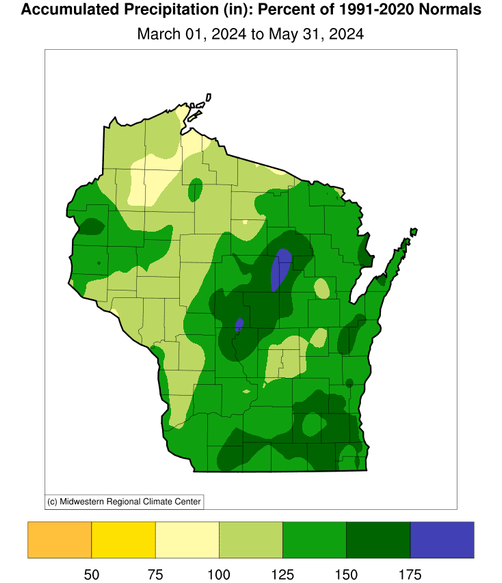

The wet, final month of spring capped an exceptionally soggy season (Figure 5) with 11.74 inches of precipitation, ranking 4th among Wisconsin’s highest totals from March to May. Throughout the spring, every month was wetter than normal, starting with a statewide surplus of 0.73 inches in March (40 percent above normal) followed by an additional excess of 0.48 inches (15 percent above normal) in April.

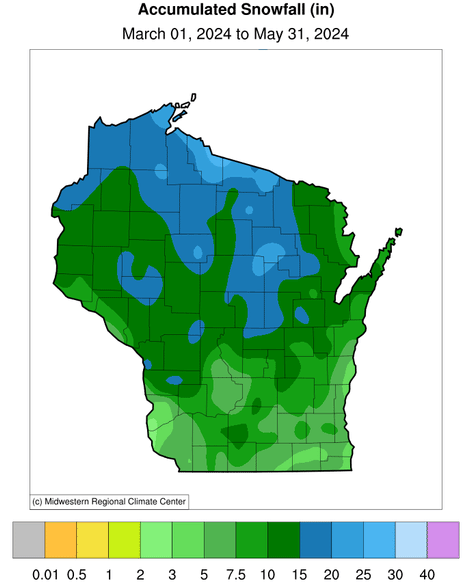

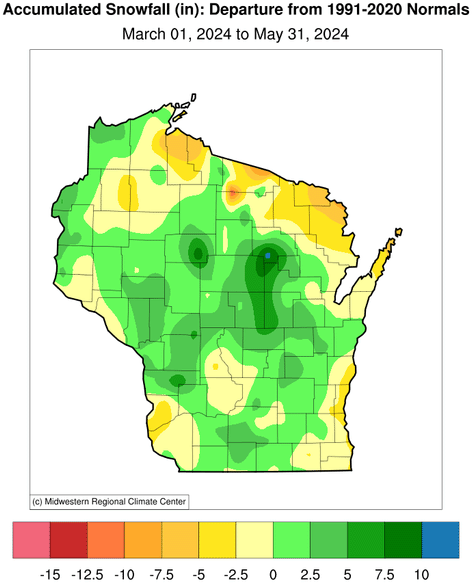

Although most of this glut came in liquid form, snow also contributed. Spring snowfall was heaviest in northern Wisconsin, where more than 15 inches fell in many places, but the anomalies were more positive in central regions (Figure 6).

Wet springs are nothing new for Wisconsin: three of the four wettest on record have occurred this century (2004, 2013, 2024), and the state’s seasonal precipitation has increased over the long term by 1.5 inches (20 percent increase) since records began in 1895. Surprisingly, the resulting moist soils did not delay spring planting on the whole: by the end of May, crops statewide were ahead of their five-year average planting dates by up to one week, according to USDA’s Crop Progress and Condition Report.

Quenching the Drought

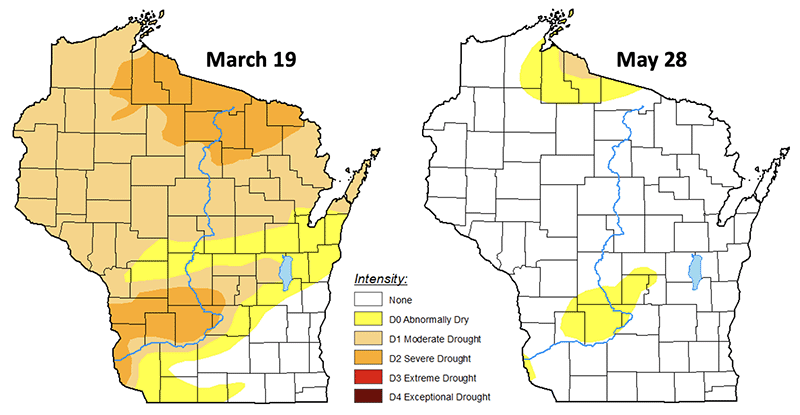

Our wet spring has led to a dramatic alleviation of drought conditions in Wisconsin that emerged last June and persisted ever since. The U.S. Drought Monitor depicted maximum drought conditions last September, followed by improvement during autumn, but then a secondary peak in the middle of March due to the dry late-winter season. A comparison of the Drought Monitor between March 19 and the final springtime map on May 28 shows this striking change (Figure 7).

Most of Wisconsin was experiencing moderate or severe drought as of mid-March, leading to worries that the dry pattern might create another difficult growing season and an early and volatile wildfire season. In fact, the number and extent of wildfires in the state as of the middle of March was more than 10 times higher than normal. But Wisconsin’s drought virtually disappeared by late May, with only a small residual patch remaining in Iron and Ashland Counties covering less than one percent of the state. With that, the rapid emergence that characterized last year’s “flash drought” has been bookended by almost as abrupt an ending across nearly the entire state.

May’s Storminess

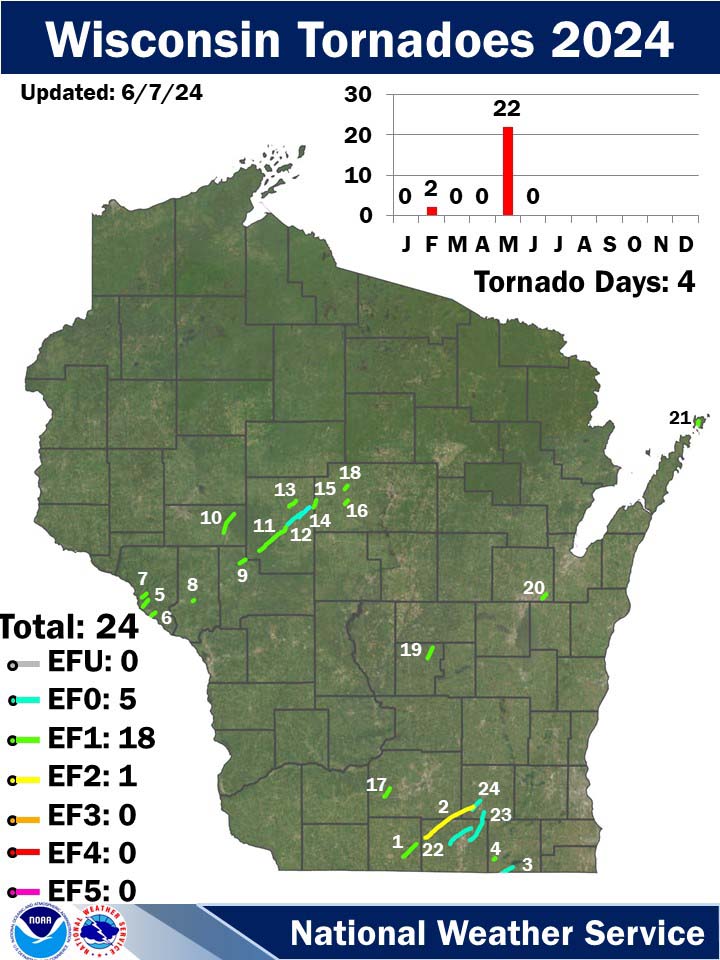

Severe weather was uncommon throughout March and April, aside from a couple of rounds of storms and strong winds. However, as May rolled around, so did the storms. On May 7, an EF-0 tornado and a short-lived EF-1 tornado occurred in Walworth County. The EF, or Enhanced Fujita, ratings were assigned based on the highest wind speed that occurred within the damage path, where EF-0 and EF-1 tornadoes have three second wind gusts of 65 to 85 and 86 to 110 miles per hour, respectively. On May 18, a few wind and hail reports were spread throughout central and north-central Wisconsin.

Unfortunately, the atmosphere destabilized the afternoon and evening of May 21, creating widespread strong winds, localized areas of hail, and 16 tornadoes. Of those 16 tornadoes, one was the first tornado to ever occur on Washington Island since official records began in 1950. Another tornado leveled a roughly one hundred year old barn near Cochrane. Near Hollandale in Iowa County, 80 mile-per-hour straight-line wind gusts crumpled several large grain bins.

Astonishingly, Madison Gas and Electric (MGE) reported this was the most widespread power outage in the city and surrounding area — 42,000 MGE customers lost power — since the Great Ice Storm of 1976. Luckily, Wisconsin was spared the amount of destruction that Iowa and Illinois experienced on this date, with no lives lost and no injuries sustained.

To kick off the Memorial Day weekend, a lightning strike presumably caused the steeple to catch on fire at the Holy Redeemer Church near Madison’s Capitol Square. On Sunday the 26th, as a line of thunderstorms approached south-central Wisconsin, three EF-0 tornadoes were formed over portions of Rock and Jefferson Counties (Figure 8).

With such an active weather pattern, there were 22 confirmed tornadoes in May, which is the second most during any May since 1950. The number one May remains May of 1988 with 24 tornadoes, all of which occurred on Mother’s Day. Wisconsin’s 2024 tornado count is up to 24, including the first two February twisters on record (Figure 9), already more than Wisconsin’s annual average tornado count of 23.

| Date | County | Location | EF rating | Length | Width | Deaths/injuries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb. 8 | Green | Albany | 1 | 8.35mi | 50yd | 0/0 |

| Feb. 8 | Rock, Dane, Jefferson | Evansville | 2 | 26.2mi | 750yd | 0/1 |

| May 7 | Walworth | Fontana-On-Geneva | 0 | 5.23mi | 50yd | 0/0 |

| May 7 | Walworth | Darien | 1 | 0.98mi | 50yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Buffalo | Cochrane | 1 | 3.93mi | 75yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Buffalo | Fountain City | 1 | 2.95mi | 50yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Buffalo | Buffalo City | 1 | 2.78mi | 45yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Trempealeau | Arcadia | 1 | 0.86mi | 75yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Jackson | Alma Center | 1 | 3.14mi | 75yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Eau Claire | Augusta | 1 | 9.7mi | 90yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Clark | Humbird | 1 | 9.45mi | 300yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Clark | Loyal | 0 | 12.3mi | 100yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Clark | Greenwood | 1 | 4.24mi | 150yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Clark | Loyal2 | 0 | 6.22mi | 75yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Clark, Marathon | Unity | 1 | 3.53mi | 65yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Marathon | Fenwood | 1 | 2.11mi | 60yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Dane | Springdale | 1 | 4.74mi | 75yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Marathon | Edgar | 1 | 2.13mi | 80yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Marquette | Neshkoro | 1 | 5.27mi | 60yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Outagamie | Kaukauna | 1 | 2.68mi | 80yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Door | Washington Island | 1 | 2.28mi | 90yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Rock | Milton | 0 | 12.2mi | 50yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Rock, Jefferson | Lima Center | 0 | 15mi | 50yd | 0/0 |

| May 21 | Jefferson | Lake Koshkonong | 0 | 5.57mi | 30yd | 0/0 |

Celestial Spectacles

Some Wisconsinites were treated to a beautiful show put on by the aurora borealis in the very early hours of May 11 and 12 (Figure 10). Greens, reds, purples, and blues danced in the night sky as charged particles from the sun’s atmosphere floated through Earth’s atmosphere. If you didn’t get the chance to view the lights this time around, you may get another chance as scientists are estimating that we are nearing the maximum period in the sun’s 11-year cycle of solar activity.

Smoky Skies

Unfortunately, smoke arrived on May 12 from fires in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, reaching unhealthy air quality levels for much of the northern United States, including Wisconsin. In the northern part of the state, the smoke was dense, causing sore throats for many folks on Mother’s Day. Some haze was even visible in far southern Wisconsin.

Outlook

In keeping with the year-long streak of record-breaking global temperatures, the National Weather Service’s summer outlook for July to September shows elevated chances of above-normal temperatures throughout the entire continental United States. Excessive seasonal heat is likely in regions colored dark orange and red in Figure 11, which encompasses a considerable portion of the country, especially the West and Southwest.

Locations in light orange, including all of Wisconsin, lean toward an unusually warm rest of summer (probability of more than one third but less than one half). Figure 11 also indicates that much of the western U.S. is leaning toward a dry season ahead, which would conspire with the heat to constitute a double whammy for promoting drought.

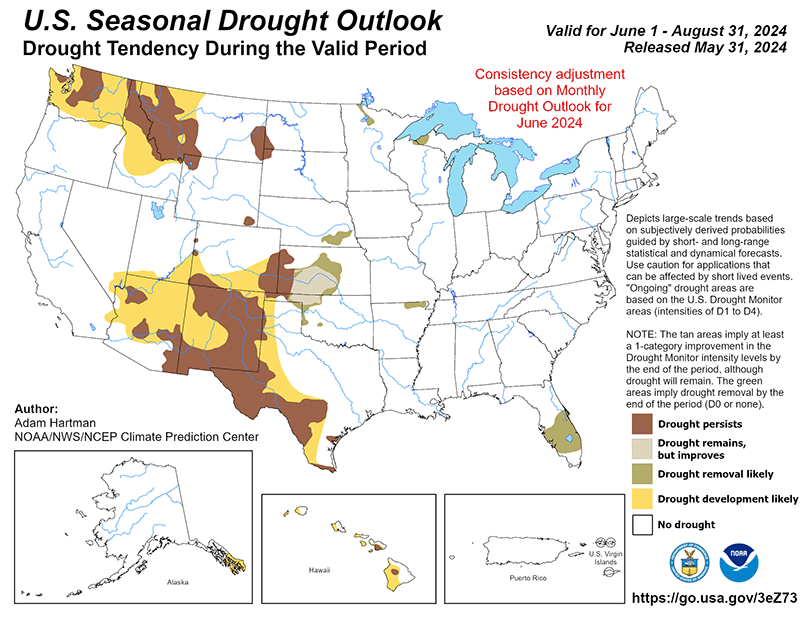

Across Wisconsin and most of the Midwest, by contrast, there are equal chances that rainfall amounts will be below, above, or near normal during the upcoming months. The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for the summer depicts that the remaining bit of drought in Iron and Ashland Counties is likely to be removed and drought development is not likely across the rest of Wisconsin (Figure 12).

Climate Corner

While tornadoes are often thought to be a sign of spring weather, they are typically most frequent and intense in Wisconsin during June, the first month of meteorological summer. The transition from winter to summer ushers in the meteorological ingredients required for tornadoes: warm, humid air masses beneath relatively cold air and an active jet stream aloft. Five of the 10 deadliest tornadoes in state history have occurred during June, including some that rank in the highest intensity category (F5 or EF5) of the Fujita or Enhanced Fujita scales, generating winds of over 200 miles per hour.

One of the most powerful was an F5 tornado that leveled the village of Barneveld (Iowa County) on June 8, 1984. It was the strongest tornado anywhere in the nation that decade. Wisconsin’s deadliest tornado in history (and the country’s ninth deadliest) with 117 fatalities occurred on June 12, 1899, in New Richmond (St. Croix County). This event is dubbed the “Circus Day Tornado” because it coincided with a circus performance that brought thousands of people to the small farming community when the tornado struck.

Steve Vavrus is the Wisconsin state climatologist. Bridgette Mason and Ed Hopkins are the assistant state climatologists.