Looking back, several Wisconsin summers have been beastly hot. July is most often that state’s steamiest month of the year, with an average high temperature just over 80°F. In recent years, July 2012 was notably hot, yet July 1936 remains above the rest.

This discussion will explore the setup that led to, the impacts of, and the innovations resulting from one of Wisconsin’s — and the nation’s — hottest months.

Setting the Stage

In July 1936, the Badger State and surrounding states across the Midwest suffered not only from stifling heat but also from extremely dry conditions that enhanced the warmth, creating the infamous Dust Bowl.

Simultaneously, the nation was digging its way out of the Great Depression. These two events, along with the heat wave, had a major impact on the nation that lasted for decades.

Tracking the Heat

The intense heat of July 1936 was the result of a heat dome that spread across the nation’s midsection, starting at the beginning of the month and continuing for the following three weeks.

During the early days of July 1936, daily surface weather maps showed a large area of high pressure located over the Appalachian Mountains in the Southeast, and another situated over Oregon and Washington in the Northwest. This formation forced the jet stream northward into Canada and created the heat dome that spanned most of the country.

The western high-pressure system drifted southward over Colorado by July 13 and 14, reinforcing the dome. Winds from the south across Wisconsin helped transport warm air into the state, and combined with an abundance of sunshine, allowed for some of the highest temperatures seen in state history over those two days.

By July 16, an area of low pressure pushed across the Upper Mississippi Valley, finally disrupting the heat dome and ending the most intense heat in the Badger State.

Setting Wisconsin Records

All-Time Highs

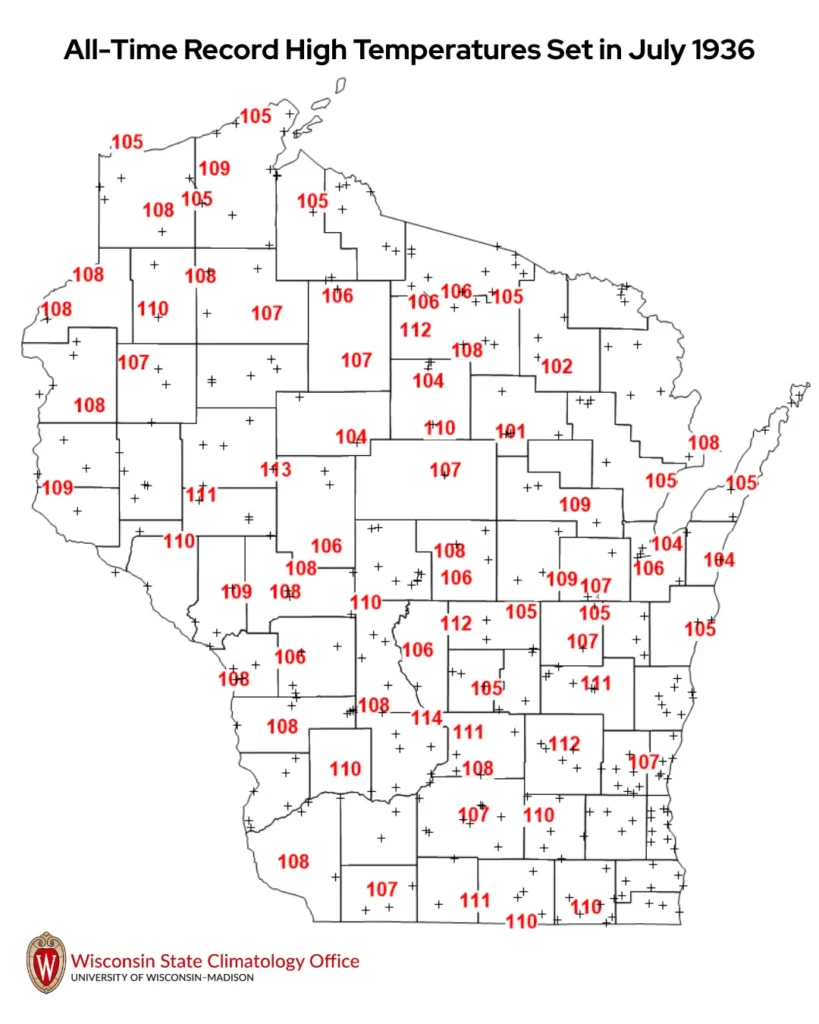

Seventy-one all-time record highs were set across Wisconsin during this heat wave (Figure 1). Because of this, July 1936 holds the record for the state’s highest monthly average maximum temperature of 89.4°F.

Of the 88 weather stations in operation across the state in July 1936, only one failed to reach triple digits. This station was the U.S. Coast Guard Station on Plum Island on the Door Peninsula, which reported a high temperature of only 94°F for the month, thanks to the surrounding cooler water of Lake Michigan.

July 13, 1936, was perhaps the hottest day ever recorded in Wisconsin since 1893. The average high temperature across the state that day was a steaming 96°F!

Wisconsin’s long-standing all-time hottest temperature of 114°F was recorded on this day in Wisconsin Dells (Columbia County).

Terrible Triple-Digits

The number of consecutive days with maximum temperatures at or above 100°F set records in Wisconsin’s first-order stations (Table 1). River Falls (Pierce County) has the dubious state record of thirteen consecutive days with triple-digit temperatures (July 7–19, 1936).

| Location | Start year of records | Hottest recorded temperatures (°F) | Longest stretch of 100°F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eau Claire | 1893 | 111 (July 14, 1936) | 11 days (July 6 – 16, 1936) |

| La Crosse | 1872 | 108 (July 13, 1995) | 9 days (July 7 – 14, 1936) |

| Wausau | 1895 | 107 (July 13, 1936) | 4 days (July 11 – 14, 1936) |

| Madison | 1869 | 107 (July 14, 1936) | 5 days (July 10 – 14, 1936) |

| Milwaukee | 1871 | 105 (July 24, 1934) | 4 days (July 8 – 11, 1936) |

| Green Bay | 1886 | 104 (July 13, 1936) | 4 days (July 7 – 10, 1936) |

No Rest for the Weary

The heat wasn’t only felt during the day: 12 Wisconsin stations reported all-time high nighttime temperatures of at least 80°F. Most notably, the temperature in Oshkosh (Winnebago County) fell to only 86°F on July 10.

Furthermore, several of the first-order stations reported a large number of consecutive nights where low temperatures remained at or above an uncomfortable 70°F. The La Crosse U.S. Weather Bureau Office (now known as the National Weather Service) had a record string of 11 consecutive hot summer nights.

Setting National Records

The 1936 heat wave is also memorable for its impressive reach across North America.

Eleven other states reached their all-time hottest temperatures during that July. Both North Dakota and Kansas saw their state record of 121°F, and the Canadian province of Manitoba reported an all-time high in July of 112°F.

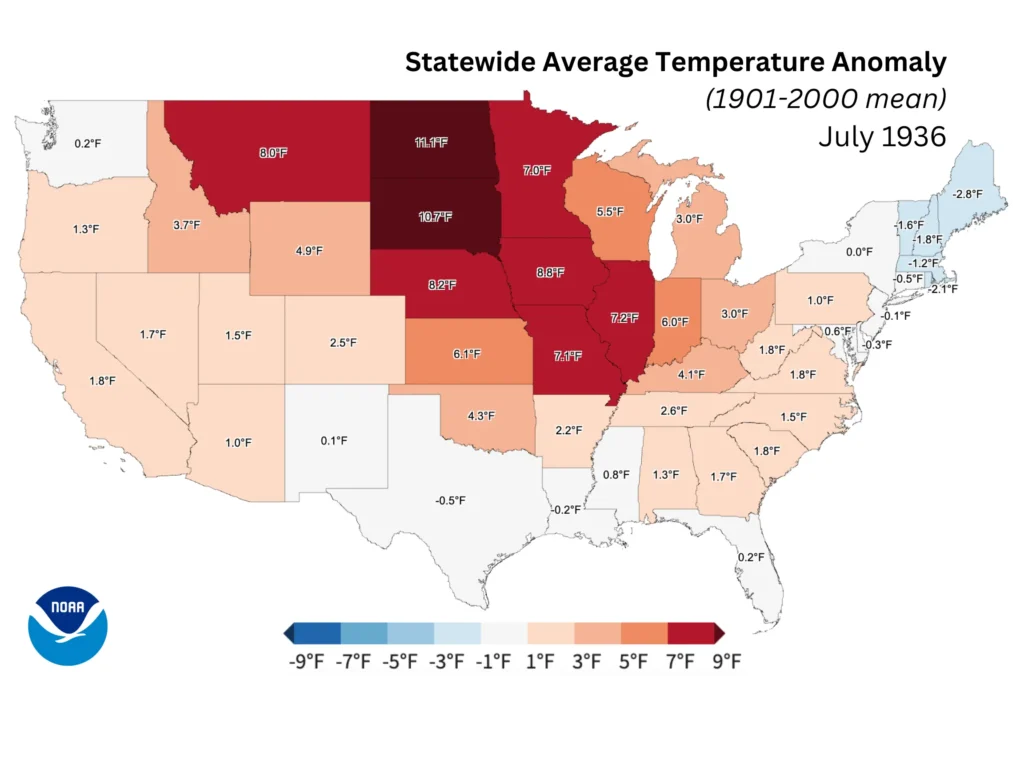

According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, whose records date back to 1895, July 1936 had both the highest maximum monthly temperature and the highest monthly average temperature across the United States during the last 131 years (Figure 2).

Heat Turns Deadly

At the time, air conditioning was an uncommon luxury in homes and often only available in select public businesses. Residents in many rural areas did not have electricity or adequate refrigeration.

Some estimates indicate that more than 450 Wisconsin residents succumbed to the heat in 1936 due to heat stroke or drowning while seeking relief in lakes and streams — likely an undercount, as heat was often considered a secondary cause of death and not reported in official records.

Nationally, the heat killed as many as 5,000 people. Some sources mark the 1936 heat wave as the second deadliest weather-related event in the country, after Texas’s infamous Galveston hurricane in 1900, which claimed more than 8,000 lives.

To the north, nearly 1,200 Canadians succumbed to the heat, the deadliest in the country’s history.

From Drought to Dust Bowl

As previously mentioned, precipitation is often hard to come by under heat domes.

While the lack of humidity was fortunate for the people trying to survive the heat, dry air sucked the moisture from the soil, exacerbating drought conditions by early summer in Wisconsin. The dry conditions intensified the summer’s extreme heat, as a dry atmosphere warms significantly faster than a moist one.

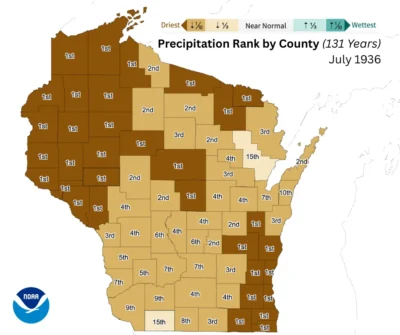

Wisconsin’s average precipitation in July 1936 was only 0.99 inches, making for the driest July in the state since 1895 (Figure 3). This record dry month came on the heels of Wisconsin’s eleventh driest June.

As the summer went on, the drought had only worsened, and rainfall deficits in Wisconsin were on the order of twelve inches by the middle of August. Statewide summer precipitation was 8.38 inches, the tenth driest since 1895.

Nationwide, summer 1936 was the second driest on record, with an average of only 6.43 inches across the 48 contiguous states. These drought conditions were responsible for the notorious Dust Bowl that spread across the nation’s midsection.

A Taste of the Southwest in the Midwest

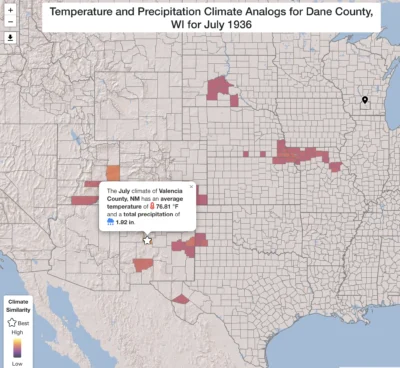

Clearly, the dry and hot conditions experienced in the Badger State in 1936 were very un-Wisconsin-like. The State Climatology Office’s Climate Analog Explorer can be used to compare variations in Wisconsin’s past climate (temperature and precipitation) to today’s average climate in other locations across the U.S.

The tool shows that Dane County’s July 1936 felt a lot more like a present-day New Mexican July climate (Figure 4)! La Crosse County was even hotter and drier, making its month more similar to southern Utah, where less than an inch of rain falls in a typical July, and the average monthly temperature is 77.6°F.

Making these connections helps to visualize the extremity of the conditions in Wisconsin during July 1936. The state’s usual continental climate was replaced with a hot and semi-arid climate more similar to that of the Four Corners region.

Ecological and Agricultural Impacts

Wisconsin’s agriculture was hit hard. The sweltering heat and a lack of adequate pasture feed resulted in the deaths of livestock, some due to sudangrass poisoning.

Milk production across the Dairy State was largely reduced, leading to a shortage of cream for butter.

The corn for silage yield during 1936 reached a record low since records began in 1919, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service. Likewise, the year’s yield for barley also remains a record low (with records starting in 1866). Nearly all strawberry and blueberry crops around the state failed.

Fish kills were documented in northern Wisconsin’s Flambeau River, caused by warm water and low water levels. Some stream gauges recorded as much as a 40 percent drop in their annual mean streamflow from their historical averages.

Learning and Adjusting for the Future

The impacts of July 1936 led to efforts to prevent an event of similar magnitude in the following years.

Drought-tolerant corn hybrids became available and had great success across the state.

The Coon Creek Watershed Project in Wisconsin was the nation’s first erosion control demonstration project. This project addressed unsustainable agricultural practices that had caused vegetation and ground cover loss, leading to soil erosion and pollution of waterways during this period.

The Wisconsin State Legislature created conservation districts within each county that focused on soil and water conservation with the passage of the Soil Conservation District Law in 1937.

To address wind-driven soil erosion caused by the extreme drought conditions, large-scale tree and shrub planting programs were created to establish shelterbelts and field windbreaks.

The Silverlining

While the catastrophic impacts of the 1936 heat and drought can’t be minimized, great strides were made to build resiliency through education, adaptation, and conservation. Further, the extent of the heat contributed to increased public awareness of the dangers of heat-related health risks.

This is a product of the Wisconsin State Climatology Office. For questions and comments, please contact us by email (stclim@aos.wisc.edu) or phone (608-263-2374).