One could be forgiven for forgetting September marked the start of meteorological fall. In Wisconsin and beyond, the continued historic hot and dry conditions sure felt more like mid-July.

Hot and Dry Early, Then Beneficial Rains

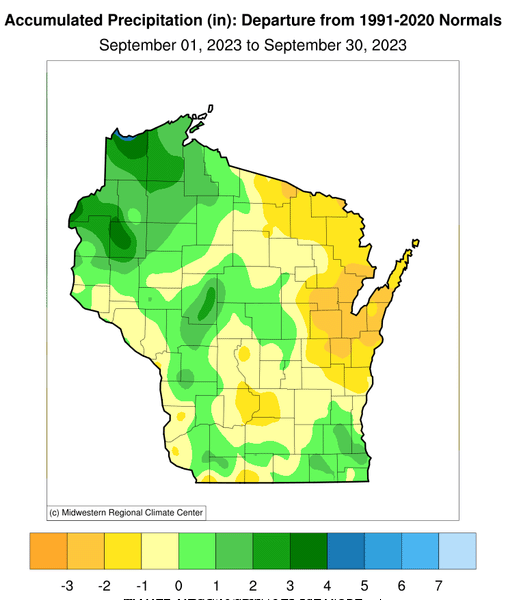

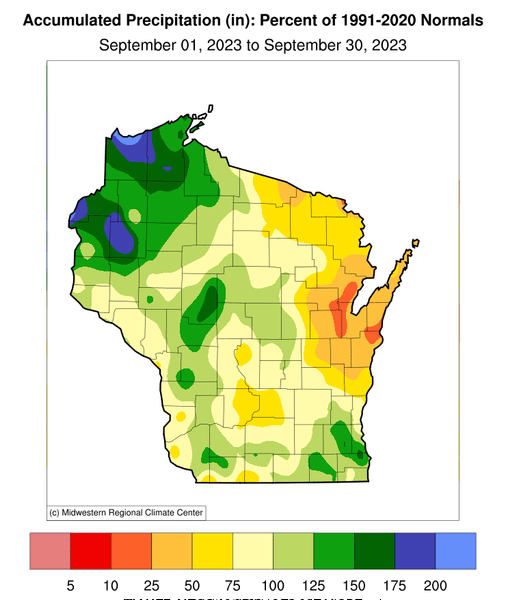

The historic drought of 2023 appears to have peaked during the middle of September, due to unseasonably hot and dry weather during the first half of the month. Although the statewide-average precipitation during September (3.52 inches) was only 0.07 inches below the 1991-2020 normal, most of that fell during the final two weeks. There was a huge spatial variation in rainfall, such that the far northwest was considerably wetter than average, while the northeast was exceptionally dry.

The substantial precipitation in the northwest was a welcome relief for this region, which was among the hardest hit by the summer drought. The wet anomalies in some areas were above 50 percent, including Douglas and Bayfield Counties, which had recently been classified in the highest drought category by the U.S. Drought Monitor. By contrast, most of northeastern and parts of eastern Wisconsin largely missed out on the rainfall, receiving less than half of average September amounts and even less than one-fourth normal in a few counties.

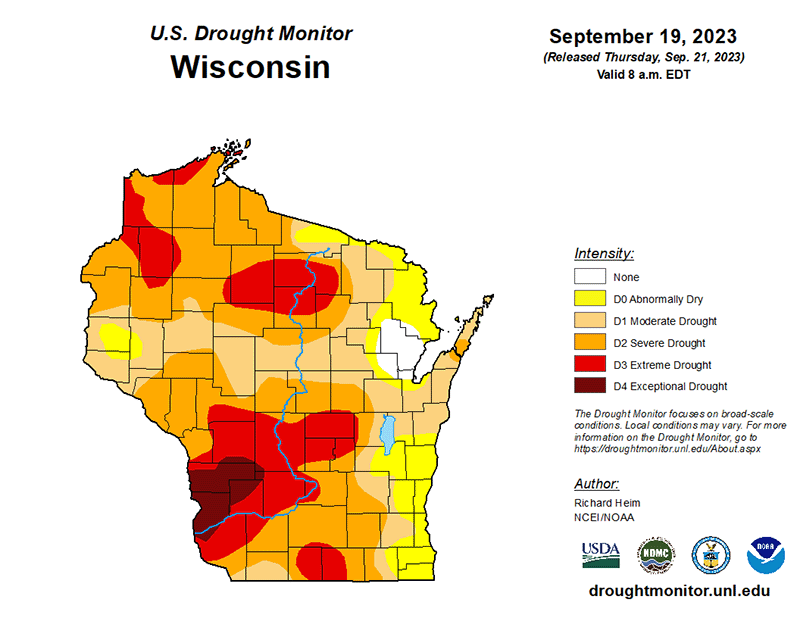

The hot, dry start to the month made the already extreme drought conditions even worse. The year’s peak drought map published by the U.S. Drought Monitor occurred on September 19, when “extreme drought” (D3 category) covered 21 percent of the state and “exceptional drought” (D4 category) occupied 3 percent. The most affected area was the southwest, but splotches of extreme drought were spread throughout the western two-thirds of Wisconsin.

Only a pocket in the northeast, centered on Oconto County, escaped any type of drought designation, although that was the state’s driest region during September.

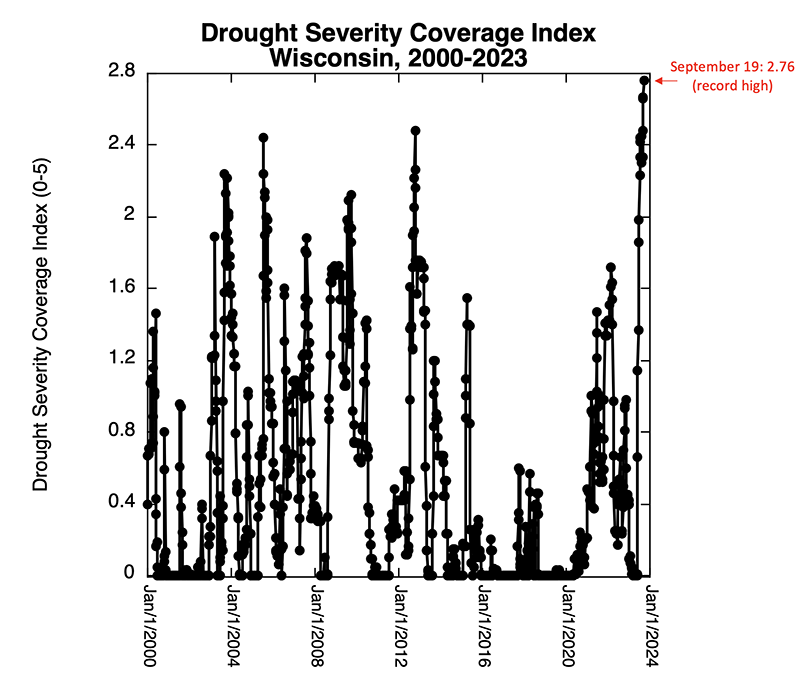

A useful measure of the combined severity and areal extent of a drought is the Drought Severity Coverage Index (DSCI) reported each week by the U.S. Drought Monitor. The DSCI is the weighted spatial average of all five drought categories across the state, after assigning a score to each:

- D0, the weakest category (abnormally dry), receives a score of 1

- D1 (moderate drought) a 2

- D2 (severe drought) a 3

- D3 (extreme drought) a 4

- D4 (exceptional drought) a 5

Therefore, Wisconsin’s DSCI can range from as low as 0 in the absence of any drought to as high as 5 if the entire state is in exceptional drought. As illustrated below, the DSCI reached its peak for the year on September 19 at 2.76, which means that the statewide average drought condition ranged between moderate and severe drought. This peak annual DSCI reading was also the highest magnitude since the U.S. Drought Monitor maps began in 2000.

In addition, the DSCI graph illustrates that this year’s drought has not only been strong but also very persistent: the DSCI continuously exceeded 2 since the first week of July and remained above this threshold throughout September.

Impacts of Drought

This year’s prolonged drought has not only been challenging for growers, but it was also responsible for other societal impacts by the end of the summer and into autumn. In mid-September the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources issued a special fire order requiring burn permits across a dozen counties. Permits were required for burning debris piles, grass, or wooded areas to lessen the threat of wildfires.

Low water levels last month caused numerous clams to become stranded along the Wisconsin River in the south-central part of the state and motivated the Friends of the Lower Wisconsin Riverway to urge volunteers to save mussels by tossing them back into the river. To the west, the Mississippi River dropped so low that barge traffic was hindered, which presented difficulties for farmers transporting their crops.

On the other hand, there were reports that farms with irrigation systems experienced a “beautiful” crop of apples and grapes this year, and the state’s cranberry harvest is expected to be above average as well.

Summer Heat in Meteorological Autumn

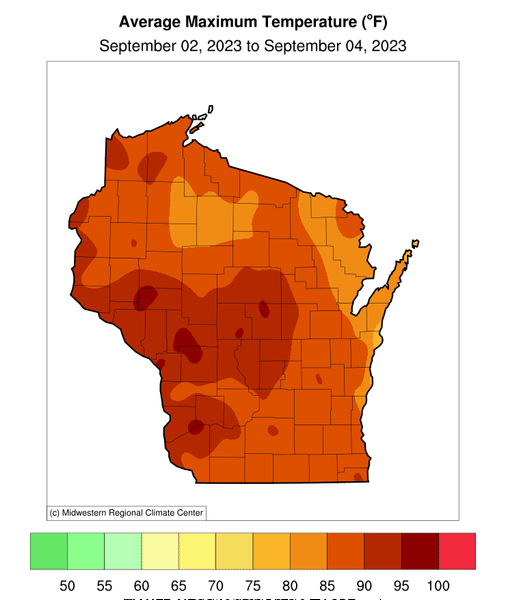

Labor Day marks the unofficial end of summer, but the holiday felt more like July 4 this year. Many parts of Wisconsin experienced high temperatures in the 90s over Labor Day weekend, with a few places repeatedly reaching the upper 90s. High winds coupled with low humidity created fire danger and prompted the National Weather Service to issue red flag warnings. Several locations even reached 100 degrees — led by a 102-degree reading in Stevens Point on September 3 — despite the calendar having flipped to September.

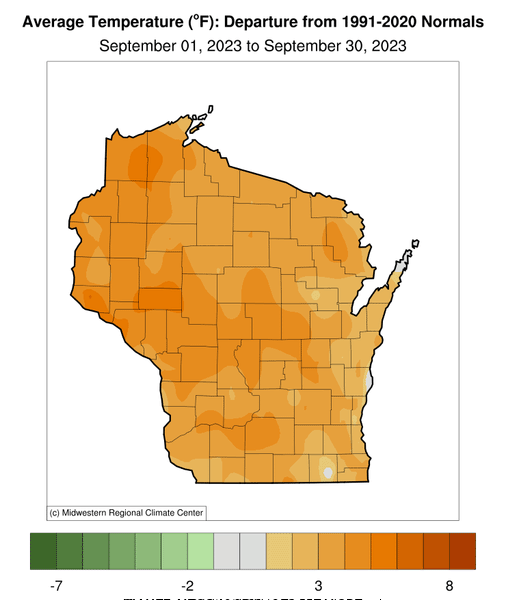

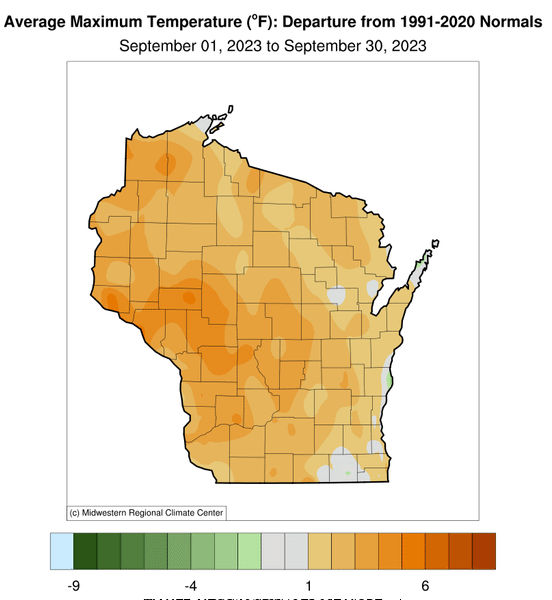

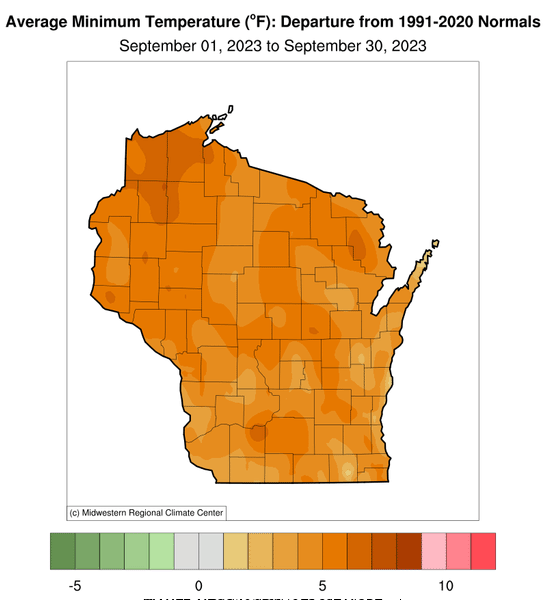

The holiday heat wave was a sign of things to come. The month as a whole was exceptionally warm, checking in as Wisconsin’s sixth warmest September on record (to 1895). The 63.2-degree average temperature was 3.7 degrees warmer than the 1991-2020 mean. Overnight low temperatures were even more remarkable: the average daily minimum temperature during September was the second warmest on record, averaging 4.9 degrees above normal (the average daily maximum was 2.5 degrees above normal, the 19th warmest).

The unusual warmth was spread throughout the state, with nearly all locations above normal. The most pronounced daily high temperature anomalies occurred in western and central Wisconsin, while the excessive daily low temperature departures were scattered but especially strong in the far northwest.

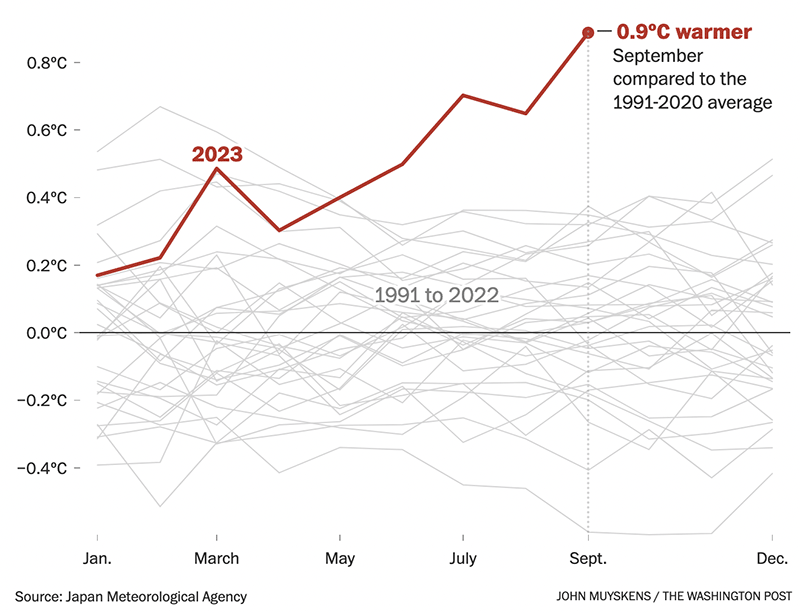

Incredibly Warm September Globally

Wisconsin’s heat last month pales in comparison with conditions elsewhere. The global average temperature was far and away the highest of any September since accurate measurements began in the 1800s and broke the previous monthly record by the largest margin ever observed. The graph below illustrates just how much of an outlier this year’s global temperature has been, especially last month.

In fact, September’s heat was more like that of a typical July, usually the world’s warmest month of the year. Only some of this startling global heat wave can be attributed to the ongoing El Niño in the tropical Pacific Ocean; surface temperatures across the other ocean basins have also been extremely high in 2023.